What kind of a person chooses to love something that is so difficult?

What kind of a person chooses to love something that is so difficult?

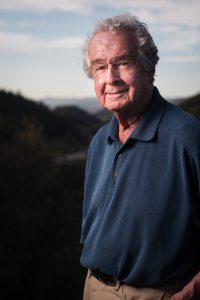

Winemakers for sure. And poets, too, remarked Warren Winiarski in one of our recent conversations. Warren was Robert Mondavi’s first winemaker and is the founder of Stag’s Leap Wine Cellars in Napa Valley. He is also the man, some would argue, who put California wines on the map when Stag’s Leap won the famed Judgment of Paris blind tasting in 1976 in France, with its 1973 Cabernet Sauvignon.

Given all of this, it would be pretty easy to be intimidated by Warren, if he were not such a down-to-earth, relentlessly curious kind of guy. Someone who will just as easily talk about history or philosophy as the optimum number of leaves on a shoot of vitis vinifera.

“The word poetry is derived from the ancient Greek ‘to make’,” said Warren, in a typical exchange of ours that began with a question about wine and moved into reflections on life, art, and even cooking. “And the things that are difficult, the things that resist your ‘making,’ those we call necessity. Every art has its own necessity, that won’t bend to your will. The winemaker, like the poet, puts up with those things – comes to loves them – in order to make beauty.”

In the past year and a half I’ve taken numerous road trips from Breckenridge to various parts of the state, interviewing winemakers for a series of articles that ran in this paper, as well as for a book on Colorado wine country. It is impossible not to be moved by the beauty of the Colorado landscape: the canyons and mesas in southwest Colorado that hold ancient cliff dwellings and eerie petroglyphs that suggest supernatural encounters; the miraculously green and fertile farmlands of Palisade tucked beneath the raw towers of the Bookcliffs; vertiginously steep vineyards in high-altitude Paonia.

Still, it is the people – farmers, grape growers, winemakers – who steal the show, with their passion and determination, fierce rivalries and grudges, their stories and their bravado, and their complete devotion to making wine in the midst of incredibly challenging geographic, weather and soil conditions.

“This land is pitiless, it is unrelentingly harsh,” said one winemaker with a vineyard in a remote canyon in Cortez. “Only a fool would try to make wine here.” Later in the afternoon, as we walked back from the vineyard to the tasting room, he paused to gaze at the plot of green and blossoming land he tends in the middle of the desert and said “When I look out at this farm, at what we have created here I think ‘there is nothing better than this’”.

On another trip, this time to Palisade, I met a winemaker who had sold his home and his business outside of Denver and moved his entire family to the vineyard he had purchased with the family’s savings. In their second winter, they lost most of the vines they had planted to frost. In the third winter they lost what little remained. And yet they stayed, and eventually their fortunes took a turn for the better. “We never once thought of leaving,” he told me, surprised that I would ask.

“We lose a lot of grapes to spring frost,” said a winemaker in West Elks, one of Colorado’s two American Viticultural Areas. “But we like to think that those grapes that survive are world class, and that with them, we make a wine with greater character.”

I asked Warren recently one of those impossible to answer questions that comes after one-too-many glasses of wine: “What is it” I said, swirling my glass, “that makes a GREAT wine?”

“Completeness” he replied, simply.

It sounded a little too easy. “What does that mean?”

“We don’t want to be dropped into an empty middle! A great wine should have a beginning, a middle, and an end.” In witnessing a piece of art, in our relationships and in our lives, he went on to explain, what we all long for is a sense of wholeness, a full experience. “A great wine,” he said, “gives us that sense of completeness.”

I can’t help thinking that if it I were Warren, I’d be sitting back with a glass of that 1973 Cabernet Sauvignon, content to spend the rest of my days gazing out over my vineyards in Napa Valley. But at 89 years old, Warren, on the contrary, is still asking questions and still intrigued by all there is to figure out. And he’ll get on a plane and travel across the country to help other winemakers pursue their quest to create something of beauty.

The last time we met, Warren had assembled a small team of wine experts in Montezuma County, Colorado, to investigate unusual growth patterns the vines seem to have adopted in a particularly rugged, windswept vineyard. He’d tasted wine made from the grapes grown in this vineyard a year ago and declared it to be “an epiphanic experience!” He wanted to understand how such an excellent wine could be produced in such unusual viticultural conditions, and he wanted to help the young winemaker and his team of growers continue their work.

Which has led me to the conclusion, after this year-and-a-half of learning a little about “the life of the vine” in Colorado’s demanding terroir, that it is not just loving something difficult and the desire to create that make life interesting and worthwhile. It is also the capacity to be curious, the willingness to get up out of your comfortable life and be amazed.

Christina Holbro ok lives in Breckenridge. | Summit Daily News

ok lives in Breckenridge. | Summit Daily News